GMO Soil, Air, and Water

Soil

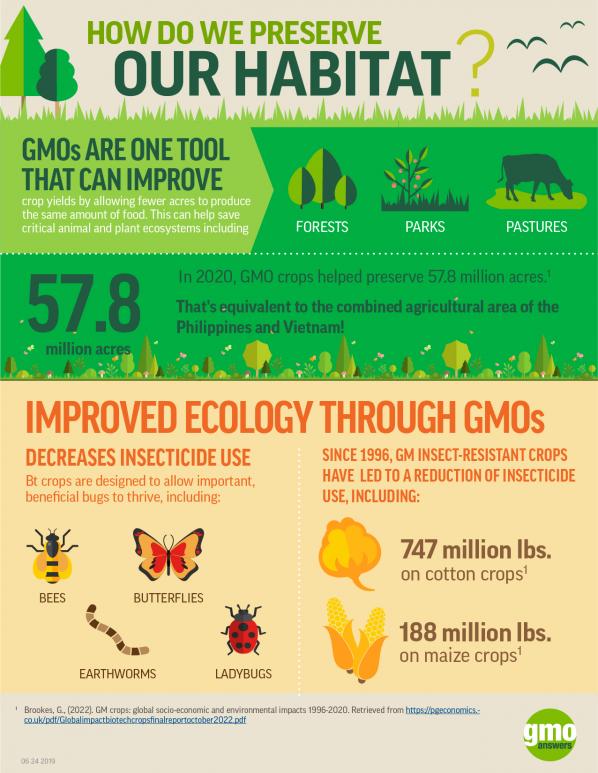

Healthy soils are the foundation of a healthy food production system and environment. From serving as a biodiversity powerhouse to contributing to carbon sequestration, healthy soils are critical to meeting the food needs of the future and keeping agriculture land productive.

Soil is home to billions of living microorganisms that recycle organic material to maintain soil fertility and support plant growth. One cup of soil may hold 7 billion bacteria – the equivalent of our world’s human population.

Globally, up to 50,000 square kilometers of topsoil – an area around the size of Costa Rica – is lost every year, mainly due to wind and water erosion. It can take more than 500 years to form two centimeters of topsoil – the outermost layer of soil, which has a high concentration of nutrients and is crucial for crop growth. Avoiding soil disruption helps keep this top layer healthy and productive, and reducing erosion into our streams and rivers helps preserve our waterways and dependent aquaculture.

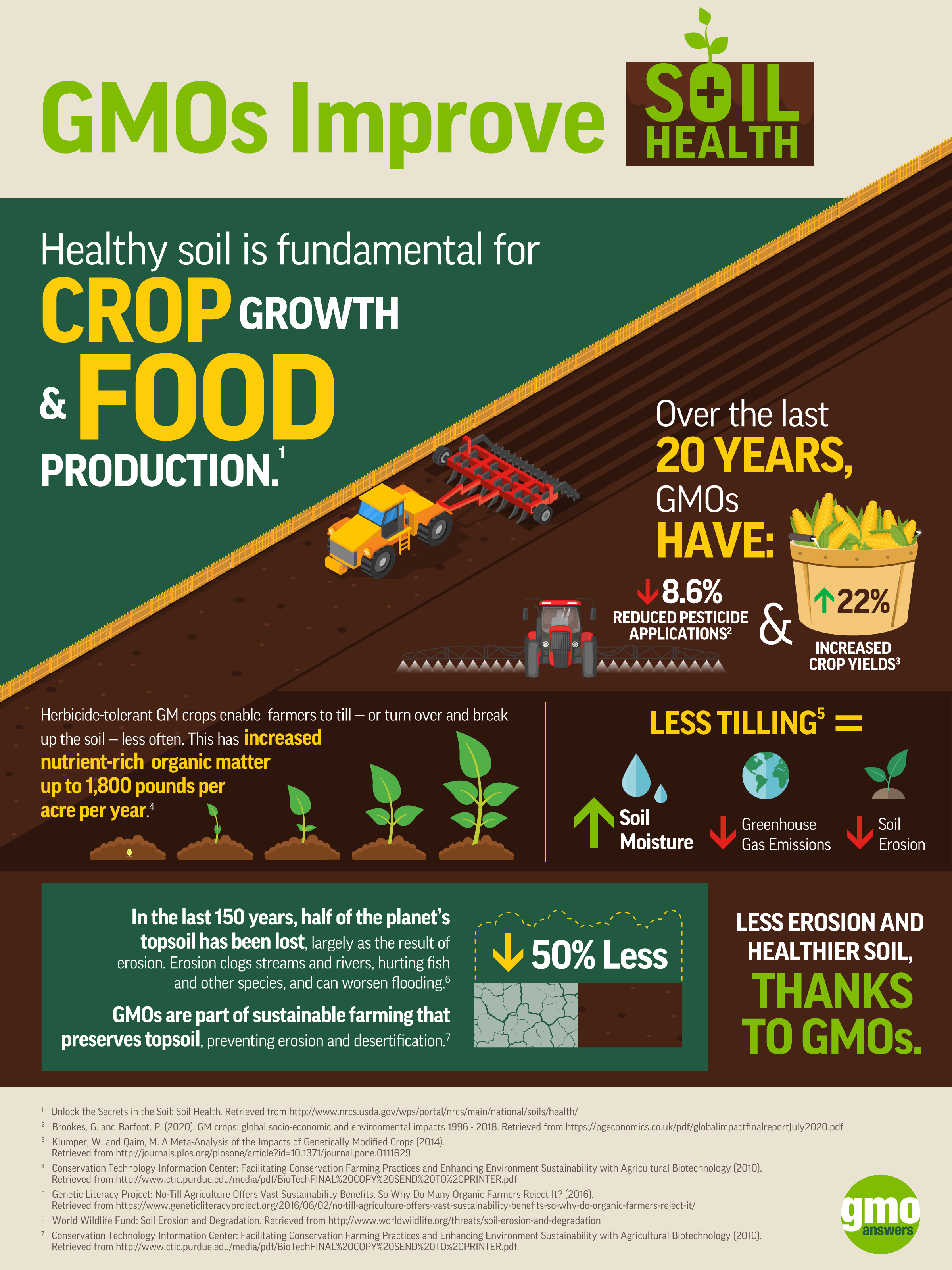

Herbicide-tolerant genetically modified crops enable farmers to till – or turn over and break up the soil – less often (conservation tillage). Florida farmer Lawson Mozley explains that with herbicide tolerant GM crops, weeds can be sprayed and left in the field to protect the soil. Then the incoming crop is planted directly into the leftover organic matter, without turning over the soil.

Less tilling means less soil erosion, as well an improved moisture retention. According to USDA, for each one percent increase in organic matter, U.S. could store the amount of water that flows over Niagara Falls in 150 days. GMOs are part of sustainable farming that preserves topsoil, preventing erosion and desertification.

Air

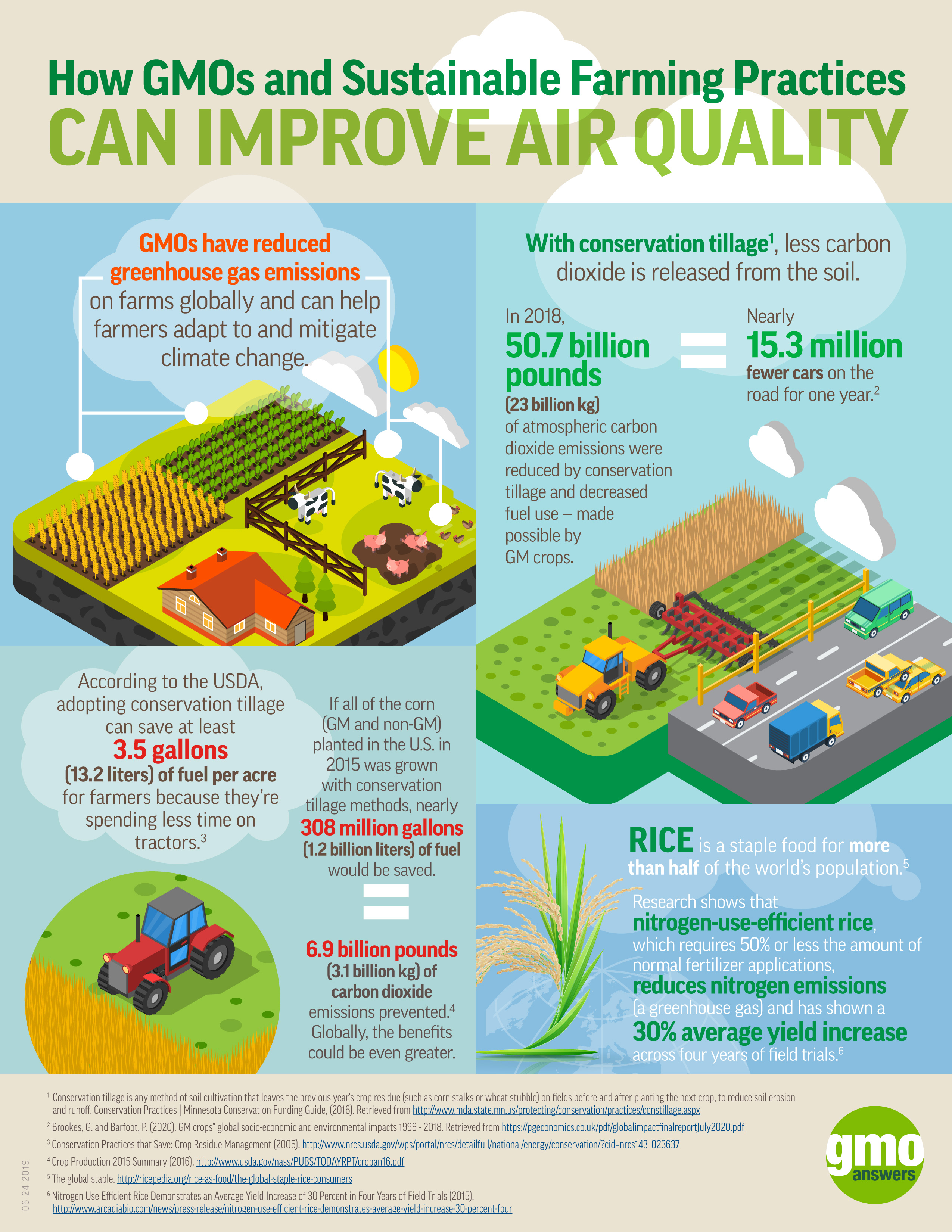

Less tilling thanks to genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops also means that farmers spend less time on their tractors, using less fuel and reducing carbon emissions. Conservation tillage enabled by genetically modified crops has reduced greenhouse gas emissions on farms globally and can help farmers adapt to and mitigate climate change. In fact, in 2018, 50.7 billion pounds of atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions were reduced by conservation tillage and decreased fuel use made possible by genetically modified crops. That’s equal to removing over 15.3 million cars from roads for one year.

According to the USDA, adopting conservation tillage can save at least 3.5 gallons of fuel per acre for farmers who would spend less time on their tractors, reducing emissions. If all of the corn planted in the U.S. (non-genetically modified and genetically modified combined) in 2015 was grown with conservation tillage methods, nearly 308 million gallons of fuel would be saved, equivalent to preventing 6.9 billion pounds of carbon emissions.

Water

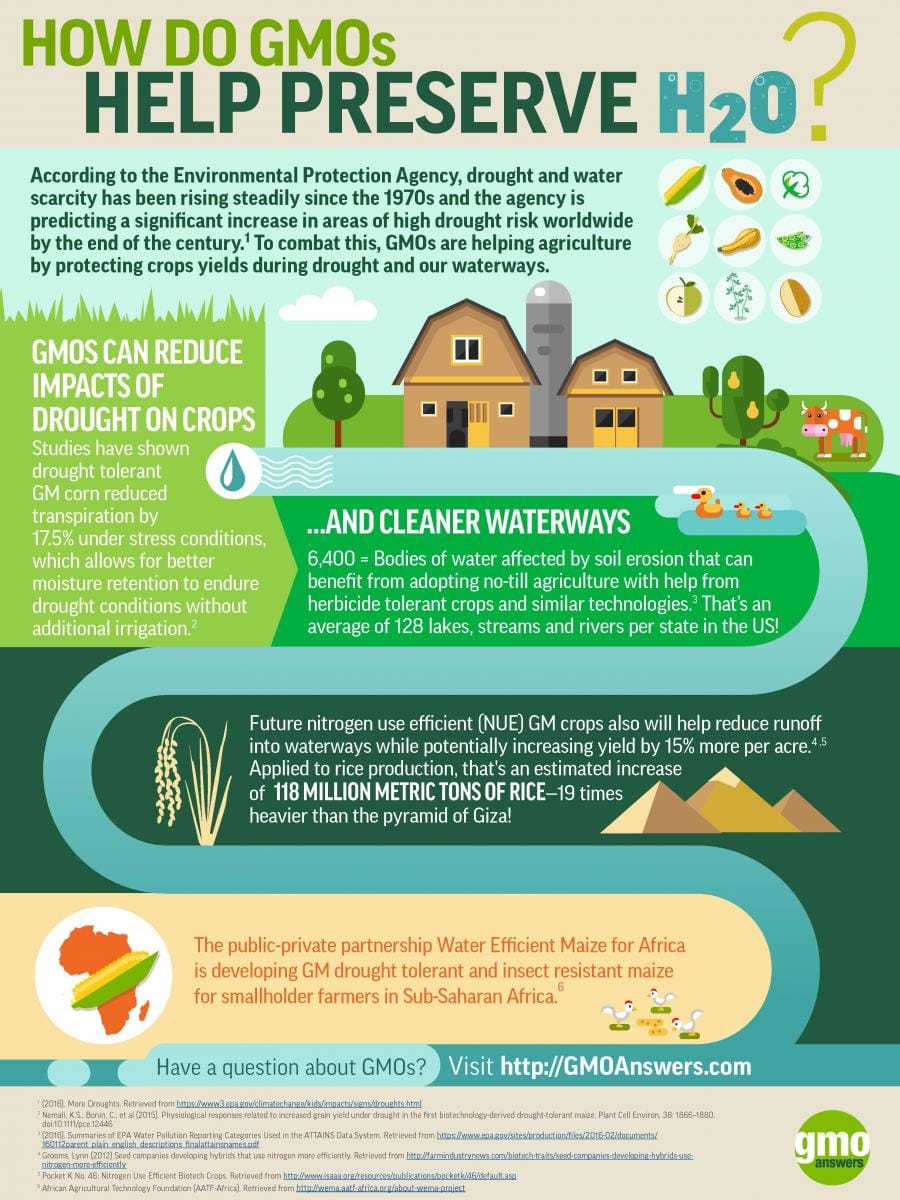

Clean and available sources of water are critical for farmers and successful agricultural production. Drought and water scarcity, which according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been steadily rising since the 1970s, is especially challenging for farmers. Genetically modified crops can reduce the impact of drought on crops and support cleaner waterways.

Studies have shown drought-tolerant genetically modified corn reduced transpiration by 17.5 percent under stress conditions, which allows for better moisture retention and the ability to endure droughts without additional irrigation. A public-private partnership in Africa is now working to develop a drought-tolerant and insect-resistant variety of corn specifically designed for the continent. It’s estimated that improved corn varieties could increase yields by 20 to 35 percent in food-insecure communities.

Additionally, no-till agriculture enabled by herbicide-tolerant genetically modified crops reduces soil erosion which can clog waterways. And future nitrogen use efficient genetically modified crops could also help reduce chemical runoff while potentially increasing yield by 15 percent per acre.

How Do GMOs Benefit The Environment?