Question

How to asses the certainty that human induced GMO crops will not have an effect in biodiversity ? Specially for cross pollinated crops like alfalfa and corn.

Submitted by: mcastillo

Answer

Expert response from Dr. Peter H. Raven

President Emeritus, Missouri Botanical Garden

Friday, 10/07/2015 13:04

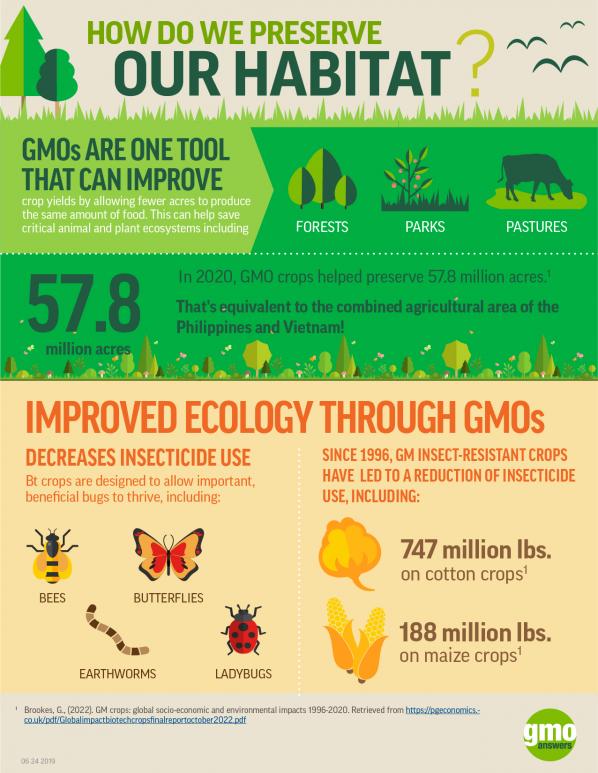

Agriculture itself has a major effect on reducing biodiversity: the conversion of about a third of the world’s land surface to croplands and pasture over the last 10,000 years has clearly been associated with hundreds of thousands of extinction events. Continuing habitat destruction, global warming, the spread of some 20,000 species of invasive weedy plants, and the selective gathering of specific plants in nature are continuing to drive many species to extinction. In that context, the relationship of various methods of improving crop species genetically – about a dozen such methods are in common use now – could have little effect on biodiversity.

For crops themselves, the modern tendency to grow large stands of homogeneous strains and to allow only certain genetic strains into commerce, as in the EU, does of course reduce biodiversity, and seed banks are the primary way to conserve the existing diversity in the face of tough demands to feed a rapidly-growing human population now at a record 7.3 billion people, half of us malnourished in some way.

For native biodiversity, the more productive the farms, the less land will be taken out of its natural or semi-natural state, and the more biodiversity will be preserved. The idea of genes getting into wild and weedy relatives of crops is valid, but not extensive. Johnson grass, a truly nasty weed, arose as a hybrid between cultivated sorghum and a weedy relative, but it is the only known case of this sort and does not involve GM methodology, by the way. Weedy sunflowers and beets infest those crops and exchange genes with them; but there are relatively few instances where wild relatives grow in the areas where crops are cultivated, and the exchange of genes is not a major problem.

Given all of the challenges to the preservation of the endowment of biodiversity that we have now, the flow of genes into natural populations or the origin of new weeds is a microscopic problem that does not deserve much emphasis among the many really important actions we could be taking to conserve biodiversity.

Answer

Expert response from Dr. Peter H. Raven

President Emeritus, Missouri Botanical Garden

Friday, 10/07/2015 13:04

Agriculture itself has a major effect on reducing biodiversity: the conversion of about a third of the world’s land surface to croplands and pasture over the last 10,000 years has clearly been associated with hundreds of thousands of extinction events. Continuing habitat destruction, global warming, the spread of some 20,000 species of invasive weedy plants, and the selective gathering of specific plants in nature are continuing to drive many species to extinction. In that context, the relationship of various methods of improving crop species genetically – about a dozen such methods are in common use now – could have little effect on biodiversity.

For crops themselves, the modern tendency to grow large stands of homogeneous strains and to allow only certain genetic strains into commerce, as in the EU, does of course reduce biodiversity, and seed banks are the primary way to conserve the existing diversity in the face of tough demands to feed a rapidly-growing human population now at a record 7.3 billion people, half of us malnourished in some way.

For native biodiversity, the more productive the farms, the less land will be taken out of its natural or semi-natural state, and the more biodiversity will be preserved. The idea of genes getting into wild and weedy relatives of crops is valid, but not extensive. Johnson grass, a truly nasty weed, arose as a hybrid between cultivated sorghum and a weedy relative, but it is the only known case of this sort and does not involve GM methodology, by the way. Weedy sunflowers and beets infest those crops and exchange genes with them; but there are relatively few instances where wild relatives grow in the areas where crops are cultivated, and the exchange of genes is not a major problem.

Given all of the challenges to the preservation of the endowment of biodiversity that we have now, the flow of genes into natural populations or the origin of new weeds is a microscopic problem that does not deserve much emphasis among the many really important actions we could be taking to conserve biodiversity.

How Do GMOs Benefit The Environment?