India’s Decision to Allow GM Crop Field Trials is a Turning Point for a Second Green Revolution

Originally posted at Truth About Trade & Technology

As a farmer in India, I am hopeful my country has reached a turning point and will finally embrace 21st-century farming, setting the stage for a second Green Revolution that is the world’s only hope for feeding 9 billion people by 2050.

As a farmer in India, I am hopeful my country has reached a turning point and will finally embrace 21st-century farming, setting the stage for a second Green Revolution that is the world’s only hope for feeding 9 billion people by 2050.

New Delhi’s recent decision to permit field trials for genetically modified brinjal and mustard represents an essential step forward—a belated decision and limited in scope, but also a move that puts India on a course for genuine progress in agriculture.

In Tamil Nadu, a state that occupies the southern tip of India where I grow rice, sugar cane, cotton and pulses on my farm, I see the significance of this struggle every day. The latest UN projections say that my country will pass China’s population within the next 15 years. If we don’t improve our food security by then, we’ll enter a period of unprecedented misery.

The good news is that much of the world recognizes the magnitude of the challenge, in India and elsewhere. In October, I participated in the World Economic Forum’s New Vision for Agriculture meeting, which convened about 120 stakeholders, including farmers, in an effort to develop strategies for sustainable agricultural growth. We discussed a wide range of subjects including the importance of technology innovation, empowerment of women and smallholder farmers, Government policies, financial services, and risk management.

Although GM crops were not a major part of our conversations, the farmers in attendance made clear that we have positive views about these crops and believe biotechnology is an indispensible part of food security. Those of us who live in the developing world would like to enjoy the same access to technology that farmers in the United States and many other countries take for granted.

In too many instances, however, our governments are still catching up with our aspirations.

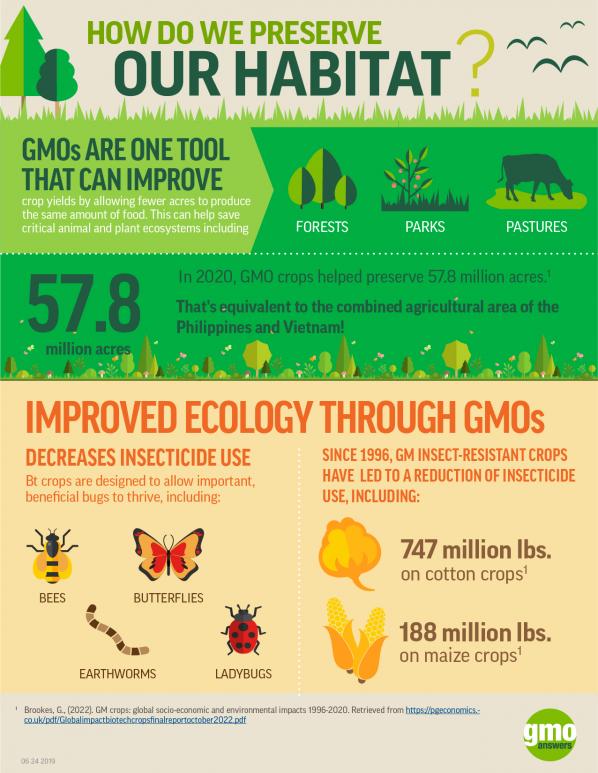

Years ago, India accepted biotechnology in agriculture when it commercialized GM cotton. At that moment, it looked like we might become full participants in a new wave of progress. Today, more than 95 percent of India’s cotton is genetically modified to resist insect pests.

This was a welcome start, but small in scale. Only a tiny minority of India’s farmers grows cotton. The rest of us produce other crops, and are yet to taste the benefit of GM crops as we try to feed a nation of more than 1.2 billion people.

Yet as farmers in North and South America pressed forward with GM corn, soybeans, and other crops, New Delhi hit the brakes. Instead of working to introduce GM brinjal—an important vegetable crop in India, known in the Unites States as eggplant—our government turned away from new forms of biotechnology.

In doing so, public officials made regulatory decisions based not on provable science, but on political science. They should have relied on reliable research from respected authorities. Instead, they responded to lies and propaganda from ideological activists.

The election of Narendra Modi as India’s prime minister earlier this year, however, appears to have changed everything. Modi’s environmental ministry, led by Prakash Javadekar, has chosen to emphasize science and technology.

India now will test some 30 varieties of GM brinjal and mustard, a decision consistent with PM Modi’s development agenda. If sound science truly animates our policies, farmers like me almost certainly will have access to better crops soon.

I’m looking forward to what happens next. I have grown brinjal in a small area, but gave up because I couldn’t keep away the pests and remain economically competitive. Many farmers in India will be benefited, if and when GM brinjal becomes available.

I plan to do everything in my power to help biotechnology take root in my country: We must make sure that successful field trials lead to commercialization, and see that our research expands to include additional crops. Today, the hard work of our Indian scientists who have developed lots of GM crops with desirable traits, including maize, rice, okra, cabbage and cauliflower, are confined to a lab while they wait for clearance from the government. This must change. It is important that these improved crops are made available to India’s farmers.

The World Economic Forum and other international organizations have roles to play as well. They can lend moral support to India’s innovators, who must continue to resist pressure from political protestors. They can also try to shape the views of opinion leaders, especially in Europe, where hostility to GM crops has encouraged India and other developing countries to question the value of biotechnology.

Most of all, however, they can encourage farmers like me to join a new Green Revolution that rises to the mighty challenge of feeding a hungry world.