Dust Bowl to Drought Tolerance: How History Leads to Innovation

This post was originally published on GMO Answers' Medium page.

As a young man on our family farm in Iowa, I can recall the many years we farmed around the wet spots because we had too much rain. Then came 1988…

The drought of ‘88 was epic, conjuring old-timer memories and images of the dust bowl during the 1930s. The frustration of watching our hard work and investment slowly wither in the field, and the drought devastate our crops, is forever a memory.

That year, average corn yields were only about 85 bushels to the acre, substantially below the normal expectation of approximately 130 bushels per acre. Honestly, my family was just happy we didn’t lose everything.

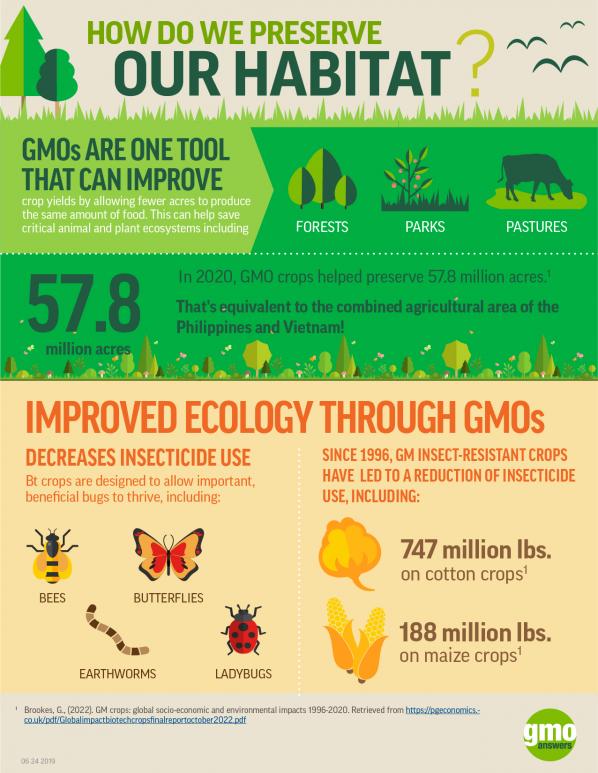

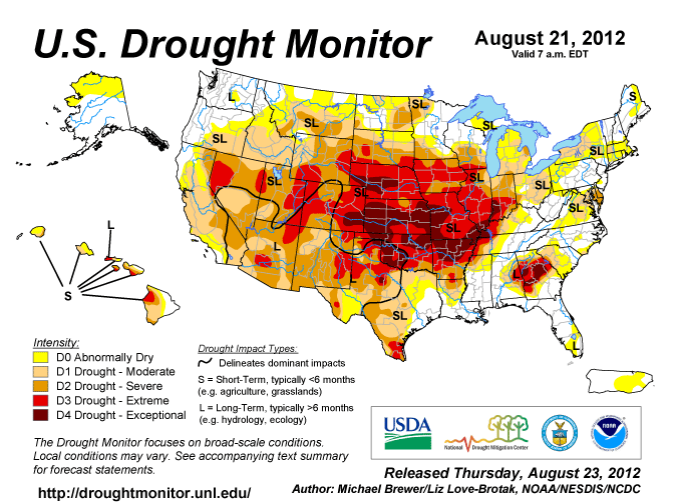

Fast forward to 2012, when I was working for Monsanto to introduce the first GMO corn trait to provide improved drought-tolerance. In that same year, the U.S. experienced another devastating drought just like the one from my youth. Fortunately, farming improved in the 25 years since the ‘88 drought. Plant breeding made the corn more drought tolerant, and GMOs enabled protection from insects and improved weed control. This enabled the adoption of widespread minimum tillage practices which kept more water stored in the soil.

The drought of 2012 was a tough year for farmers, and the agricultural industry, but these conditions provided real-time testing environments for our new drought resistant traits. By every statistic, the drought of 2012 was as bad or worse than in 1988, and yet the average corn yield was about 123 bushels per acre, 38 bushels better than in ’88. That’s progress.

Today, almost a third of the continental U.S. is experiencing a drought. More significantly, some 87 million Americans live where there’s a limited water supply. Globally, in any given year, 3.4 billion people (nearly 50 percent of the world's population) are vulnerable to water scarcity. This motivates me to do something about it.

With the frequency of drought predicted to increase as an impact from climate change, we need to look to innovative technology to adapt to more water stressed conditions. Agriculture has a big role to play as it is estimated that agriculture uses about 70 percent of the world’s available water supply.

One of the most remarkable applications of agricultural technology is the development of drought-tolerant crops. As arid weather continues, farmers are looking to water-efficient seeds to help them produce more food per unit of water.

My work at Monsanto has offered me new challenges - to help smallholder farmers in Africa get better seed to help them manage the threat of frequent drought. In 2008, we entered a public-private partnership to develop Water Efficient Maize for Africa (WEMA) funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and USAID. We are continuously working to adapt technology and share experiences from our work on drought in the U.S. to fit the African environment – this is a real solution and I get to be part of it.

WEMA is a collaborative partnership that strives to improve food security and livelihoods among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa by developing drought-tolerant maize that is adapted to African conditions. Monsanto has provided the royalty-free use of technologies for drought tolerance and insect resistance to the project so that small-holder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa can afford the newest technology in hybrid maize seed bred for and adapted to their environment.

The WEMA partnership has helped develop hybrid seed now available to African farmers under the TELA™ and DroughtTEGO™ brands. Specifically, conventionally bred DroughtTEGO™ hybrids give farmers the ability to harvest 20 to 35 percent more grain under drought conditions. These hybrids have also impacted the livelihoods of approximately 250,000 African farm families and more than 1.5 million people.

Without the adoption and use of modern agricultural technology, like drought-tolerant maize, African farmers are likely to repeat the well-known story of drought leading to drastic yield loss and food insecurity. This is an all too familiar downward spiral that can devastate families, communities and countries – again, unacceptable to me. The scourge of drought is seared in my memory from 1988. Those memories compel me to keep striving to learn more and use science and innovation to help farmers around the globe persevere through the dry years.

There are no simple solutions or a single fix to problems like water scarcity. But we know that science leads to innovation, and modern agricultural technologies will perform with demonstrated resiliency in the face of climate change. Farmers everywhere start every season full of hope. With rapid advances in science, these hopes are being realized.