Question

How is biodiversity impacted by the introduction of GM crops? Are the current set of crops being replace with a smaller, less biologically diverse set of GM crops?

If so, is there an increased risk of a much larger-scale impact from the adaptation of infectious diseases or pests?

If there are increased risks, how are scientists, businesses, farmers and regulatory agencies managing this risk?

Submitted by: gapoli

Answer

Expert response from Martina Newell-McGloughlin

Former Director, International Biotechnology Program, University of California, Davis

Friday, 02/08/2013 17:51

Wow, there are a lot of great questions here. I’ll answer them individually:

First, how is biodiversity impacted by the introduction of GM crops?

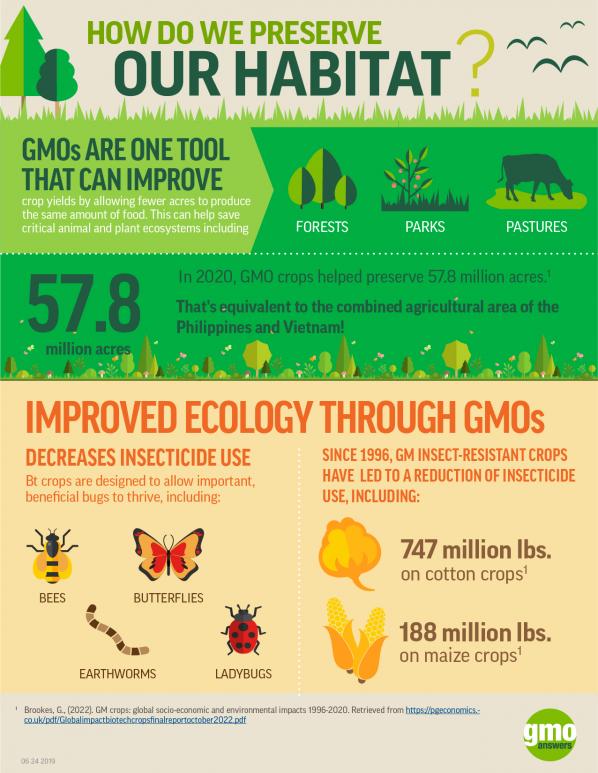

Biodiversity is actually enhanced by the adoption of GM crops. Those crops commercialized to date have reduced the impacts of agriculture on biodiversity through enhanced adoption of conservation tillage practices, through reduction of pesticide use and use of more environmentally benign herbicides and through increasing yields to alleviate pressure to convert additional land into agricultural use.

Is the current set of crops being replaced with a smaller, less biologically diverse set of GM crops?

With the introduction of GM crops, concern has been raised that crop genetic diversity will decrease because breeding programs will concentrate on a smaller number of high-value cultivars. Studies that have been done to date (cotton in the United States and India; soybeans in the U.S.) find that the introduction of GM crops has not decreased crop diversity. From a broader perspective, GM technology has the potential to actually increase crop diversity by enhancing underutilized alternative crops, and to facilitate more widespread production of heirloom varieties that have fallen out of favor because of their poor agronomic performance, pest/disease susceptibility, lesser adaptability and other undesirable characteristics. Advantageous genes can render them more suitable for widespread commercialization. In addition, transgenic approaches are being used to improve so-called orphan crops, such as sweet potato, cassava, etc., potentially increasing options and improving diversity, especially in sensitive regions.

If so, is there an increased risk of a much larger-scale impact from the adaptation of infectious diseases or pests?

Integrated pest management is an important cornerstone of any cropping system. Biotech provides a much broader, more effective set of tools that can be used with existing systems and has the potential to be rapidly deployed in anticipation of emerging diseases and altered pest pressure. In addition, gene stacking and gene rotation means that there is potential for multiple layers of protection, which should reduce pressure and ensure greater robustness and longevity in pest- and disease-resistance management. There are also fewer negative effects, such as diminished impact on non-target insects, with the non-target effects of insecticides being much greater than for Bt crops.

The introduction of herbicide-tolerant crops has facilitated adoption of conservation tillage, which has decreased erosion, increased water-usage efficiency and decreased pesticide runoff. Adopters of GM crops have reduced insecticide use and switched to more environmentally friendly herbicides. In addition to the potential benefits of expanded adoption of current technology, several technologies in the pipeline offer additional promise of alleviating the impacts of agriculture on biodiversity. Especially within the context of climate change, solutions must be developed to adapt crops to not only existing but also evolving environmental stressors, such as soil depletion and greater extremes of heat, cold, drought, flooding and salinity. Technologies to address those stressors, including drought, submergence, salinity and other tolerance, would alleviate the pressure to convert high-biodiversity areas into agricultural use by enabling crop production on suboptimal soils and enabling the return to production of depleted soils. Arguably, the most critical abiotic stress is lack of sufficient water. Unfortunately, irrigation is also one of the major causes of arable land degradation, as mineral salts that occur naturally in irrigation water accumulate over time in soils. In fact, crops are now limited by salinity on 40 percent of the world's irrigated land (25 percent of the United States). Salt-tolerant crops currently in production will allow crops to grow on land that is 50 times saltier than normal, one-third as salty as seawater. This system also addresses the increasing problem of saltwater encroachment on freshwater resources. Drought tolerance technology, which allows crops to withstand prolonged periods of low soil moisture, is anticipated to be commercialized in the near future. Nitrogen-use efficiency technology, also under development, can reduce run-off of nitrogen fertilizer into surface waters. The technology promises to decrease the use of fertilizers while maintaining or increasing yields, achievable with reduced fertilizer rates where access to fertilizer input is limited.

GM crops can continue to decrease the pressure on biodiversity as global agricultural systems expand to feed a world population that is expected to grow to nine billion by 2050 and will require a 70 percent increase in food production. So increased productivity with reduced impact on diversity is imperative for sustainability.

If there are increased risks, how are scientists, businesses, farmers and regulatory agencies managing this risk?

As noted, the risk is decreased, not increased, and subject to parameters similar to those of any other production system. So the same risk-focused management systems should be deployed to ensure proper stewardship of the earth’s resources.

How Do GMOs Benefit The Environment?