ARTICLE: Profile of an Indian GM Farmer: High-Tech Seeds on a Traditional Farm

The following is an excerpt of an article at Medium.com discussing why some farmers in India choose to grow genetically modified crops.

It is already dusk in Nimbhara — a small, nondescript village deep in the heart of India — but early morning for me. I am on a phone call with a farmer named Ganesh Nanote who has lived here all his life. Almost all of Nimbhara’s 500 or so working adults find employment as cultivators. A single road connects Nimbhara to the highway system; it was only built about eight years ago, and is now plied by a regular traffic of bicycles and three-wheeler rickshaws. Nimbhara’s heritage, culture, and industry all spring from its soil — an alkaline black heavy soil, broken down from the Deccan lava flows that might have killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

While Ganesh has fifty acres, most farmers in Nimbhara have much less. Government projects over the years have made at least some form of irrigation available to most farms, though there is still a heavy dependence on monsoon rains for water needs — monsoons that are increasingly unreliable due to climate change, Ganesh explains. Most of the population lives on less than ₹200/= [USD 3.50] a day. And yet, somehow, Indian villages like this one have become avid consumers of cutting-edge research.

Many people imagine that Indian farmers were growing native cotton using thousands-of-years-old traditions before GM cotton dragged modernity in. This is not the case. Most farmers had moved beyond native cotton because its short fiber length and low yield makes it unsuitable for what the market demands — raw cotton that can feed high-volume mechanized production of fabric. Most were already growing modern hybrids, with high yields and large bolls — that were also unfortunately more susceptible to pests. In the 1990s, before GM cotton came into the market, farmers all over the country were fighting a serious infestation of cotton bollworms. Sometimes, Ganesh told me, especially given long stretches of cloudy weather, farmers would lose more than half their cotton to it, and could not harvest enough to cover their costs.

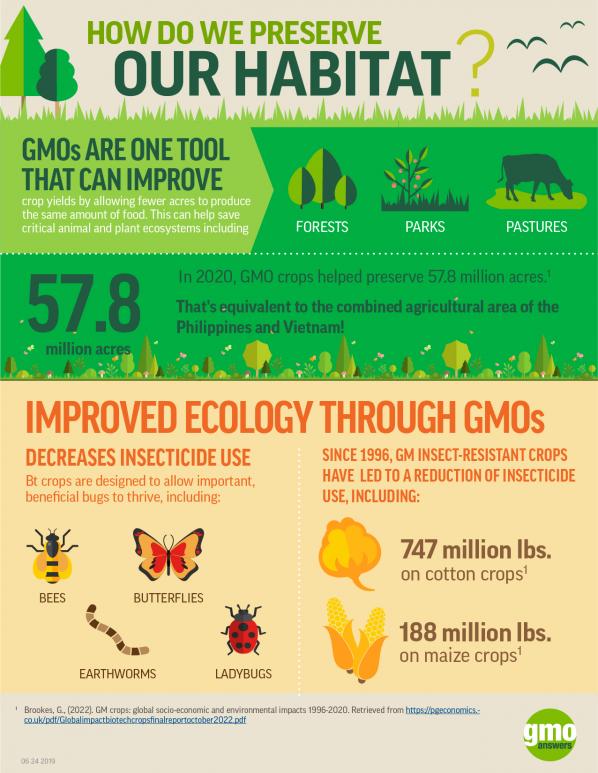

This is why the promise of a cotton crop that came with its own insecticide created such a buzz. While chemical pesticides work like bulldozers, mowing down all life, scientists now favor biological controls that are targeted towards specific pests. For instance — the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), that has been used as an organic pesticide for more than five decades, works in a surgical fashion, much like a key for a lock. It is not toxic until it enters the guts of its target — moth and butterfly larvae — where it causes them to starve to death.

To read the entire article, please visit Medium.com.