In December 2018, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) finalized the standards for mandatory “GMO” labeling by releasing the “National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard” (or NBFDS). The NBFDS establishes the rules of the road for disclosing which foods in the U.S. have been or may have been bioengineered (BE) and is enforced by the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), a sub-agency of the USDA.

GMO labeling has been a contentious topic for many years. Anti-GMO activist groups have traditionally pushed for a “warning” on foods that could be “contaminated” with GMOs. On the other hand, scientists, food companies, and farmers who create and grow GMOs generally pushed back on mandatory labeling of a food produced with biotechnology, because mandatory labels in the U.S. have historically been used to identify health or nutritional information. GMO foods, however, have been proven to be just as safe and nutritious as their non-GMO counterparts, therefore needing no “warning” labels. Between these two poles, consumers have grown increasingly interested in learning more about the food they eat, including information about foods produced with biotechnology. In fact, data shows that 3 in 5 consumers want to know more about GMOs.

USDA’s final labeling standard for bioengineered food is an important solution for consumers. First, the labeling standard acknowledges that many people want to know if the foods they are consuming were derived from “GMO” (bioengineered) crops. Just as importantly, the standard provides this information without frightening imagery that could lead consumers to believe GMO/BE food is labeled because it is something to be concerned about or avoided entirely. About GMO/BE labels, USDA explicitly states:

“Nothing in the disclosure requirements set out in this final rule conveys information about the health, safety, or environmental attributes of BE food as compared to non-BE counterparts. In fact, the regulatory oversight by USDA and other Federal Government agencies ensures that food produced through bioengineering meets all relevant Federal health, safety, and environmental standards.”

GMO labeling may take effect as early as February 2019, but is mandatory for all retail food products that are bioengineered or contain bioengineered ingredients by January 1, 2022.

Why ‘bioengineered’ and not ‘GMO’?

Bioengineered may be a new term for many consumers, but it is honestly a much better term for the 10 “GMO” crops commercially available today in the U.S., as well as the few other crops currently in production, though not yet available for purchase, or already commercially available in other countries. (Read the full list of bioengineered foods at AMS.USDA.gov)

The acronym GMO literally stands for “genetically modified organism.” While “GMO” is the most commonly used term for crops bred through transgenesis, the breadth of this term has been creating a good deal of confusion for the average consumer who may not have a deep understanding of farming or food production. After all, in the 1900’s roughly 40% of the U.S. workforce was involved directly in agricultural production. Today that number is just 2%.

The term “GMO” creates confusion because virtually everything we eat has had its genes modified in some way, whether through very traditional plant breeding processes or through more modern means of seed breeding. The four main methods of seed improvement used to create the foods we eat today include:

- Selective breeding, which humans have been doing for thousands of years. Bananas, broccoli, and citrus all come from selective breeding.

- Hybridization/cross-breeding, which humans have been doing for over 200 years. Seedless grapes and watermelons are created this way, as are most apples and all that produce that sounds like hybrids – pluots, tangelos, etc.

- Mutagenesis for seed improvement started in the 1920’s. Mutagenesis uses radiation and other mutagens (physical or chemical) to induce random mutation in plants, activating new, desirable varieties, like the deep color and signature flavor of Ruby Red grapefruits.

- Transgenesis, which is what people typically mean when they talk about GMOs. Transgenic crops have precise, limited genes added or silenced through bioengineering to achieve a beneficial outcome, like reduced food waste through non-browning or significant, positive environmental impacts through herbicide tolerance or pest resistance.

What these four seed improvement techniques all have in common is that genes in the food change—they all have been genetically modified at some level. Some modifications happen in the thousands (mutagenesis) and some are limited to 1 or 2 genes (transgenics).

This means that “GMO” or “genetically modified” is simply too vague of a phrase to talk about one type of breeding technique, potentially referring to any or all of them. “Bioengineered” or “BE” gets much closer to the foods consumers are actually trying to learn about – transgenic crops or the foods, fuels, and fibers derived from them.

Who and what needs to disclose bioengineered food ingredients?

A bioengineered food is defined by USDA as “a food that contains genetic material that has been modified through in vitro rDNA techniques and for which the modification could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature.” Labels for these foods are now mandatory under the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard.

In the simplest terms, any food intentionally containing genetic material derived from GMO alfalfa, canola, corn, cotton, papayas, potatoes, soybeans, squash, sugarbeets, or Arctic™️ Apples must bear a BE label.

A few other foods need to or will need to be labeled as well. Bt eggplant from Bangladesh is required to bear the label, but since the U.S. prohibits imports of eggplants from Bangladesh at this time, it is unlikely the label will be seen on this food. Future foods that contain genetic material derived from pink-fleshed pineapples or AquAdvantage® salmon – neither of which are commercially available yet, but are currently in legal production – will also require labeling. The USDA will review the list of bioengineered foods annually and make any needed updates based on new crop approvals in the U.S. and around the world.

While that is the general rule, there are a few nuances and exceptions that are critical to know:

- This labeling law applies to foods that are subject to the labeling requirements under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). GMO crops are used to make a ton of non-food products, spanning from gasoline to blue jeans. These are not under the jurisdiction of the USDA’s Agriculture Marketing Service (AMS), and as such are not mandated to be labeled.

- BE-labeled food must include genetic material. Whole food products like corn or edamame contain DNA, but highly refined foods like corn syrup or soy sauce do not. Because there is no genetic material present in highly refined foods – GMO or not — they are not required to bear a BE label.

- Some things we consume – like vodka – are regulated by different government agencies. Alcohol is regulated by the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (and for the most part does not contain genetic material), and is likely not subject to this labeling regulation—with the exception of wines with less than 7% alcohol by volume and beers brewed without malted barley and hops.

- The genetic modification of bioengineered food products could not have been obtained through other breeding techniques. This means hybrid crops or crops made by mutagenesis or through selective breeding, such as pluots—even though their genes have certainly been modified—are not required to bear a BE label.

Here’s the one big caveat:

There are a bunch of other food labeling regulations and standards already in place in the U.S. for meat, poultry and eggs through the Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA). The primary ingredient of any food determines which agency’s labeling regulations must be followed. If the primary ingredient (or second, if the first is water or broth) would independently be subject to labeling under the FDCA, the product must follow AMS' labeling standard. If a product is made with meat as the primary ingredient, it is subject to FMIA’s labeling standards and regulations, and will not be required to use the AMS BE label. However, that product could be voluntarily labeled; many producers have been voluntary disclosing for years.

There are a few exemptions to the National Bioengineered Food Labeling Standard.

In addition to the cases above where AMS’ GMO disclosure is not applicable, there are a few cases in which BE labeling is exempted. Those exemptions are as follows:

- Incidental additives do not need to be disclosed. This could include enzymes, yeast, and rennet, among others. Incidental additives are already excluded from inclusion on ingredient lists (as outlined by the FDA), as they have no functional or technical effect, are processing aids, or are migrated from equipment or packaging. However, if a bioengineered yeast, enzyme or other organism doesn’t qualify as an incidental additive it would most likely require disclosure.

- Food served in a restaurant or similar retail food establishment (e.g., a food truck, bar or cafeteria) and very small food manufacturers (<$2,500,000 annual receipts, which is the same exemption for other USDA and FDA regulations) are exempt.

- Food certified under the National Organic Program. Organic certification and the bioengineered labeling standard are regulated by the same agency within USDA, the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS). To meet the USDA Organic regulations and receive certification, farmers and processors must show – among other things – that they aren’t using GMOs. Therefore, Certified Organic label is enough to tell consumers what they want to know about GMO content in these foods.

- Animals fed bioengineered (GMO) feed, and their products. This exemption directly addresses questions and claims about the impact of GMO feed on meat, milk, eggs, and other animal products. Not only has “GMO” DNA never been detected in any meat, eggs or milk from livestock, there is no reason to believe it would, because that’s not how digestion works. When humans or animals eat food that contains DNA or proteins, they are “released” from the food and processed by the digestive system in the gastrointestinal tract. The same way eating chicken doesn’t make you cluck or grow feathers and eating spinach doesn’t make you green, animals (human, livestock, or otherwise) that eat GMO crops don’t absorb that DNA into their bodies.

As with all food in the U.S., there are thresholds set for inadvertent or technically unavoidable presence of bioengineered substances. Any intentional presence of BE substances must be disclosed no matter how much is present, but the threshold for inadvertent or technically unavoidable bioengineered substances is 5% which “…appropriately balances providing disclosure to consumers with the realities of the food supply chain.”

Voluntary labeling is allowed.

Foods that are not subject to the national labeling standards but whose manufacturers, importers, or retailers want to disclose these ingredients anyway have the ability to do so voluntarily, provided they adhere to guidelines established under the NBFLS.

The same labeling standards and disclosure guidelines for foods that are required to disclose must be used – where they go, what they say, what information is provided. This ensures consistency for consumers.

Where to look for bioengineered disclosures

There are specific presentation guidelines for disclosing bioengineered ingredients that must be followed to ensure standardized information about foods that contain GMOs is accessible to anyone at any time. BE food disclosure must be “conspicuous” – big enough and placed where anyone could reasonably see it on the packaging – and can take the form of on-package text, an electronic or digital link, SMS/text messaging, or through the use of one of the four below symbols.

Symbols

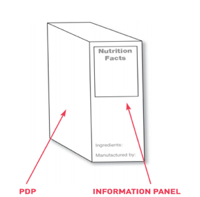

These symbols are meant to be placed on the information panel (near where you find nutritional information), on the front of the package, or in the most conspicuous location possible.

Text

A package can have text printed that displays clear disclosure statements like “Bioengineered Food” or “Contains a BE Food Ingredient.” The limitation to text is that it cannot say “may” – “may” include, “may” contain, etc. It is all or nothing – something either contains genetic material that has been bioengineered, or it doesn’t.

Electronic

A QR code may be used to direct consumers to a website that contains information about BE ingredients. If a QR code is used, it must include clear language, like “scan here for more food information,” and must also provide consumers with a phone number they can call. Any website or phone number connected to labeling disclosure cannot collect personal information or provide consumers with any marketing material. This website and phone number must be active 24/7, 365 days a year.

SMS/text message

Food manufacturers, importers, and retailers can provide a number that consumers can text message for information. Again, this number cannot collect any personal information or be used in any way for marketing. This number must be active 24/7, 365 days a year.

For very small packages

If a package is simply not large enough to house any of the above material, a shortened version of the required disclosure statement can be used, or a URL can be provided.

Deciphering common food labels

Label overload is a real thing; we encounter an overwhelming amount of often confusing and conflicting information on or about the foods we shop for, but not everything on or about the food you eat is about health, safety or nutrition. There’s a big difference between nutritional information and marketing lingo, and sometimes it’s hard to know the difference.

Some labels—like “Certified Organic”—*feel* better for consumers, but an Organic label has nothing to do with safety, health or nutrition. Organic agriculture is defined as “...the application of a set of cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that support the cycling of on-farm resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.” It is one of several farming practices; Organic isn’t about growing healthier or safer crops, it’s just a different way of growing them.

Other labels—like “bioengineered”—may *feel* less good, as if the label exists so you can avoid something that could be harmful. This couldn’t be further from the truth. A bioengineered label also has nothing to do with safety, health or nutrition, it is simply a way to give consumers the information they have asked for.

“Nothing in the disclosure requirements set out in this final rule conveys information about the health, safety, or environmental attributes of BE food as compared to non-BE counterparts. In fact, the regulatory oversight by USDA and other Federal Government agencies ensures that food produced through bioengineering meets all relevant Federal health, safety, and environmental standards.”

There are also a whole host of labels created by private companies and manufacturers that are not government regulated. While the FDA prohibits labels that mislead consumers, explicitly prohibiting labeling that implies any food is “safer, more nutritious, or otherwise has different attributes than other comparable foods because the food was not genetically engineered,” the popular (and problematic) Non-GMO Project has made an industry out of exploiting consumer fear by convincing the public that GMOs are contaminants to be avoided and advocating that consumers should choose foods with their labels to avoid them — all while charging producers and consumers a premium for those labels. These “butterfly” labels, and the message that GMOs are less than other foods, are extremely problematic, as they willfully defy established government labeling standards and ignore the overwhelming scientific consensus that GMOs are as (or more) safe and nutritious as their non-GMO counterparts.

So how is the average consumer supposed to decipher all of these different messages on and about food, and know what is about health and safety and what is just marketing or informed choice? Nutritional information is always displayed on the information panel. By federal law, it must include anything you need to know about the health implications of what you are eating, including nutritional content, ingredients and known allergens. Other nutrition content claims (e.g., low fat) are also dictated in detail by the FDA. If you want to know if the food you are eating is healthy for you, look here. If you want to know how it was bred or grown, look for the Organic or Bioengineered label, found adjacent to the information panel or on the front of the package.

So how is the average consumer supposed to decipher all of these different messages on and about food, and know what is about health and safety and what is just marketing or informed choice? Nutritional information is always displayed on the information panel. By federal law, it must include anything you need to know about the health implications of what you are eating, including nutritional content, ingredients and known allergens. Other nutrition content claims (e.g., low fat) are also dictated in detail by the FDA. If you want to know if the food you are eating is healthy for you, look here. If you want to know how it was bred or grown, look for the Organic or Bioengineered label, found adjacent to the information panel or on the front of the package.

If you have questions about the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard that this post doesn‘t answer for you, we encourage you to submit them!