Question

What is the history of the phenomenon of Monsanto being a focal point for opponents of GMOS? Did antiGMO sentiment predate the Monsanto is literally hitler conspiracy theories or did the two develop in tandem?

Submitted by: Bunabhucan

Answer

Expert response from Community Manager

Tuesday, 25/11/2014 13:12

I really like this question and am often asked why Monsanto is a focal point for opponents. An effective way to rally people to a cause is to have a villain. A good story needs a villain, a victim and a hero. The best villain has a face; for instance, Seinfeld popularized that many people are scared of clowns, but American Horror Story personified it with Twisty. Monsanto represents the personified villain, rather than one less defined (i.e., the biotech industry as a whole). So pick the company that was first on some of the technology milestones, add in a few legacy issues (Agent Orange, DDT) and some of the earliest business practices that may be difficult to understand (e.g., farmer agreements), and you have a villain. And since Monsanto sold Roundup, opponents even get to claim that GM was invented just to sell more Roundup, in spite of the fact that some companies that sell Roundup Ready seed don’t sell Roundup and many companies besides Monsanto sell glyphosate.

I thought I’d start with 1986, before I worked for Monsanto, since I personally witnessed Jeremy Rifkin say that he would see to it that recombinant bovine somatotropin (rbST) would never be approved. This is a protein produced by cows that is more prevalent in the blood of high-producing cows. When cows are supplemented with rbST, they increase milk production and improve efficiencies of dairy farms. I remember thinking that there was a growing body of research on the physiology of bST but that it was odd that Rifkin would make such a statement, since very little was known about the application of bST as a potential commercial product at that time. Rifkin, in my mind, started the anti-biotech movement. Most of the studies at that time were narrowly focused on milk yield and were too small to draw conclusions about health. His major concern at that time was the economics of small farms, but he failed to point out a major advantage of this product — that little capital investment would be required.

Let me explain: many farm technologies are very expensive and can require a large investment of capital: for example, a new tractor, which can cost up to $1 million, or purchasing more cows ($2,500 each), then building a better/bigger barn to house them, etc. These things are costly, and small farms might not have the access to this kind of capital; however, rbST and the cost of each application was the same whether a farmer had 10 cows or 1,000.

But, Rifkin knew how to use assertions about safety to get attention. Although at least four companies did regulatory studies with bST in the 1980s, Monsanto was the first to publish extensive studies, many of which were rolled out in a meeting in 1990, and was the only company to get FDA approval and commercialize this product. So it was only logical that Monsanto would have been a target of the early application of biotechnology in agriculture.

A similar thing occurred with GM crops. In 1994, the Flavr Savr tomato became the first whole food that was developed using biotechnology, and, as he did with bST before much was known about it, Rifkin proclaimed that the Flavr Savr tomato would be dead on arrival. In row crops, Monsanto, led by Robb Fraley, was the first company to report the expression of foreign genes in plants. Two other labs, led by Van Montagu (Ghent University) and Chilton (Syngenta), reported similar work, which eventually led to these three scientists’ getting the World Food Prize in 2013. Then, in 1996, Monsanto scientists were the first to publish a study, which was not even required for regulatory approvals, reporting results of feeding Roundup Ready soy to different animal species, which was mischaracterized in the movie The World According to Monsanto.

A great way to illustrate the value of personifying the villain is through questions that we’ve seen on GMO Answers. Early in the development of this site, the most frequent question had to do with Monsanto employees’ not eating GM-derived food in the cafeteria; although it was answered many times, the question came up again just recently. This is a way to insidiously suggest that Monsanto people (the villains) know the dangers and don’t care. But this is a completely unfounded claim that is driven by social media and the recipients of this message who choose to believe it. It still surprises me that people believe impractical conspiracy theories like this.

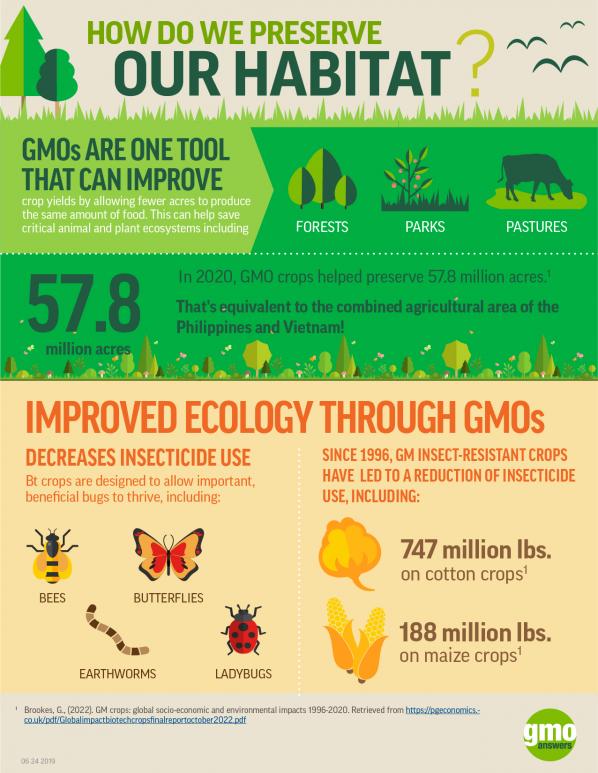

I grew up in a city and wanted to get into agriculture after reading Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock because of undeniable problems — the population continues to exponentially grow, so many people do not have access to balanced meals, and, on a personal note, I’d like to see wildlife preserved by not bringing more acres of land into agriculture. I work with more than 20,000 employees that worry about this everyday and are dedicated to cooperatively interacting with other scientists from other companies, regulatory organizations and universities to find solutions.

One last point: the villainous Monsanto Company is routinely voted as a great place to work. I find the disconnect between the narrative that others tell about us and what I experience as an employee to be very interesting and telling.

How Do GMOs Benefit The Environment?